It’s been seven and a half years since my dad died, and while I don’t really think about him every day, I do think of him often, and occasionally dream something that he’s a part of, and laugh about something I know he would find funny.

So Father’s Day is different now. Mostly I encourage our daughter to remember the day is coming; I also thank my husband and my brothers for being such great dads. If I’m in a mood, I will say to my husband, “Well, I don’t have to do anything for Father’s Day because my dad is dead.” Like I said – when I’m in a mood.

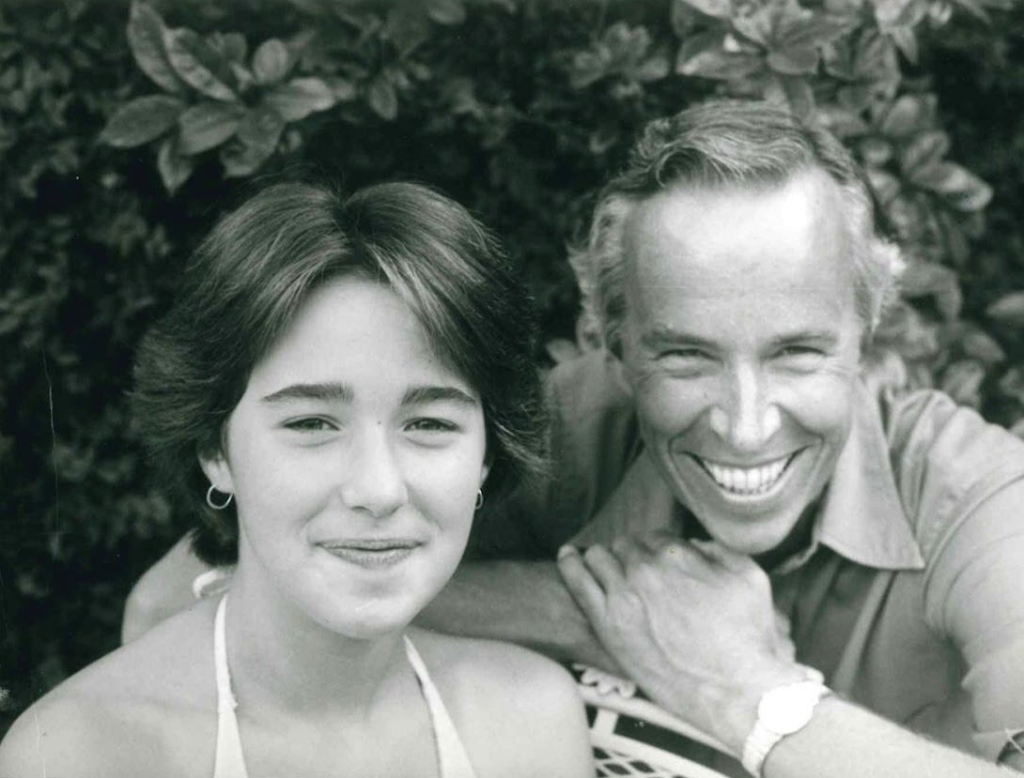

But today, Father’s Day, I’ve been thinking about my dad and a few memories stand out.

The first is when he taught me to ride a bike. It is a visceral memory, full of emotion, which must mean something since it happened 55+ years ago. We went to the parking lot of my elementary school in Morristown, New Jersey, my hot-pink, banana-seat bike in the back of the station wagon, just me and Dad. He did not believe in training wheels (later, when I was an adult, he would say that training wheels were for candy-asses.) He ran along side me as I wobbled along, holding the handlebars, not letting ago until I found my balance, and then he let go, still running beside me. I don’t know why this has stayed with me all these years. Maybe it has something to do with fear and courage and encouragement and protection and love all wrapped around the asphalt pavement of Hillcrest Elementary School.

The second memory is from my teen years, which were not the smoothest in terms of our relationship. We’ll leave that there but perhaps you can fill in your own blanks about rough patches with a parent. This story is not about that.

When I was eight we moved from New Jersey to Houston – the flatland of humidity and flying cockroaches. There are good things about Houston, but this story is not about that. Anyway, we had not had flying cockroaches in New Jersey and let’s just say they terrified me. Spiders? Bring ’em on! Flying cockroaches? More correctly, palmetto bugs – I would not enter a room where I could see one. It was my habit, when entering a room where there was a cockroach, to get my dad to come kill it, which he did. One night, after he had gone to bed, I went to the bathroom to wash up for the night. There, on the wall behind the toilet, was a big ol’ shiny cockroach. Dad had gone to bed. He hated being woken up. I knew I would not be able to brush my teeth, much less sleep in my connecting room, knowing that roach was just waiting to crawl all over me. So I went in to my parents’ bedroom, woke up my dad, told him the problem. He got up and told me to get a magazine or newspaper, which I did. He strode into the bathroom, whacked the cockroach which fell straight into the toilet, flushed it away, and wished me a goodnight.

He loved to tell me that story. I’m not sure if it had to do with my trusting him to take care of things or with his amazing aim, but it was one of his favorites.

The last memory is from my young adulthood. My parents had moved back to New Jersey and I was living and working in New York City. I had landed what I thought was my dream job – assistant to the artistic director of an arts organization, the perfect jumping-off spot for someone who wanted to go into arts administration, which I did at the time. After five months, my dream job had become a nightmare. I would wake up at 2am on Saturday nights worrying about it, wondering what I had forgotten to do, wondering what my boss would yell at me about on Monday.

I had gone to my folks’ house for the weekend and we talked about everything. Dad finally said to me, with all the wisdom of someone who had had his own career ups and downs, “No job is worth this, honey.” Not long after that, I quit as my boss was firing me, and while my future became less certain, my heart was much happier.

Seven and a half years ago, as Dad was nearing the end of his life, the time came for me to say goodbye to him. That remains the most excruciating thing I have ever done, and if you’ve had to do that, you understand. I told him I loved him, and I thanked him – for teaching me how to ride a bike, for killing cockroaches, for letting me know it was okay to walk away from something; for encouraging me never to carry a credit card balance and to set aside ten percent of every paycheck for savings (that didn’t happen); for being pleased as punch when I told him I was pregnant, for welcoming my husband and then our daughter into the family; for pointing out, every time we sat on the deck of the cabin, how beautiful the cottonwoods were shimmering in the breeze.

Now when I sit on the deck of the cabin, and look at the cottonwoods shimmering in the breeze, I laugh a little, and look up at the sky, and say thank you once again.

I ran home at lunch today to burn last year’s palm leaves. It’s a funny smell and my neighbors might have wondered just what the minister next door was doing. Nothing untoward, truly – unless you consider taking a symbol of honor and life (the palm) and burning it to ashes to remind people that they are oh, so mortal untoward.

I ran home at lunch today to burn last year’s palm leaves. It’s a funny smell and my neighbors might have wondered just what the minister next door was doing. Nothing untoward, truly – unless you consider taking a symbol of honor and life (the palm) and burning it to ashes to remind people that they are oh, so mortal untoward.

For Jack, Annie, Tom, and Grace

For Jack, Annie, Tom, and Grace